Exponential function

In mathematics, the exponential function is the function ex, where e is the number (approximately 2.718281828) such that the function ex equals its own derivative.[1][2] The exponential function is used to model phenomena when a constant change in the independent variable gives the same proportional change (increase or decrease) in the dependent variable. The function is often written as exp(x), especially when the input is an expression too complex to be written as an exponent.

| Exponential Function | |

| Representation |  |

| Inverse |  |

| Derivative |  |

| Indefinite Integral |  |

The graph of y = ex is upward-sloping, and increases faster as x increases. The graph always lies above the x-axis but can get arbitrarily close to it for negative x; thus, the x-axis is a horizontal asymptote. The slope of the graph at each point is equal to its y coordinate at that point. The inverse function is the natural logarithm ln(x); because of this, some older sources refer to the exponential function as the anti-logarithm.

Sometimes the term exponential function is used more generally for functions of the form cbx, where the base b is any positive real number, not necessarily e. See exponential growth for this usage.

In general, the variable x can be any real or complex number, or even an entirely different kind of mathematical object; see the formal definition below.

|

Overview

The exponential function arises whenever a quantity grows or decays at a rate proportional to its current value. One such situation is continuously compounded interest, and in fact it was this that led Jacob Bernoulli in 1683[3] to the number

now known as e. Later, in 1697, Johann Bernoulli studied the calculus of the exponential function.[3]

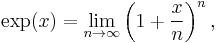

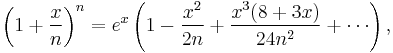

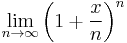

If a principal amount of 1 earns interest at an annual rate of x compounded monthly, then the interest earned each month is x/12 times the current value, so each month the total value is multiplied by (1+x/12), and the value at the end of the year is (1+x/12)12. If instead interest is compounded daily, this becomes (1+x/365)365. Letting the number of time intervals per year grow without bound leads to the limit definition of the exponential function,

first given by Euler.[4] This is one of a number of characterizations of the exponential function; others involve series or differential equations.

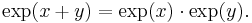

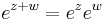

From any of these definitions it can be shown that the exponential function obeys the basic exponentiation identity which is why it can be written as ex

The derivative (rate of change) of the exponential function is the exponential function itself. More generally, a function with a rate of change proportional to the function itself (rather than equal to it) is expressible in terms of the exponential function. Explicitly, for any real constant k, a function f: R→R satisfies f′ = kf if and only if f(x) = cekx for some constant c. This function property leads to exponential growth and exponential decay.

The exponential function extends to an entire function on the complex plane. Euler's formula relates its values at purely imaginary arguments to trigonometric functions. The exponential function also has analogues for which the argument is a matrix, or even an element of a Banach algebra or a Lie algebra.

Formal definition

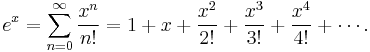

The exponential function ex can be characterized in a variety of equivalent ways. In particular it may be defined by the following power series[5]:

Using an alternate definition for the exponential function leads to the same result when expanded as a Taylor series.

Less commonly, ex is defined as the solution y to the equation

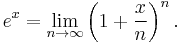

It is also the following limit:

The error term of this limit-expression is described by

where, the polynomial's degree (in x) in the term with denominator nk is 2k.

Derivatives and differential equations

The importance of exponential functions in mathematics and the sciences stems mainly from properties of their derivatives. In particular,

That is, ex is its own derivative and hence is a simple example of a pfaffian function. Functions of the form kex for constant k are the only functions with that property. (by the Picard–Lindelöf theorem) Other ways of saying the same thing include:

- The slope of the graph at any point is the height of the function at that point.

- The rate of increase of the function at x is equal to the value of the function at x.

- The function solves the differential equation y ′ = y.

- exp is a fixed point of derivative as a functional.

In fact, many differential equations give rise to exponential functions, including the Schrödinger equation and Laplace's equation as well as the equations for simple harmonic motion.

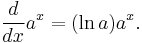

For exponential functions with other bases:

Thus, any exponential function is a constant multiple of its own derivative.

If a variable's growth or decay rate is proportional to its size — as is the case in unlimited population growth (see Malthusian catastrophe), continuously compounded interest, or radioactive decay — then the variable can be written as a constant times an exponential function of time.

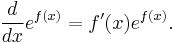

Furthermore for any differentiable function f(x), we find, by the chain rule:

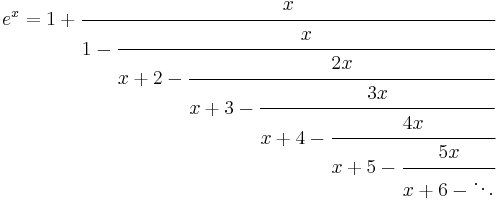

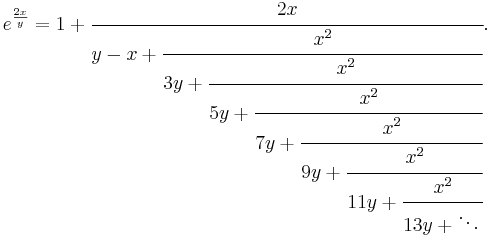

Continued fractions for ex

A continued fraction for ex can be obtained via an identity of Euler:

The following generalized continued fraction for e2x/y converges more quickly; for x = y the first partial denominator will be zero but this does not stop convergence:

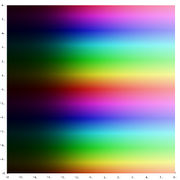

Complex plane

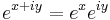

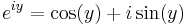

As in the real case, the exponential function can be defined on the complex plane in several equivalent forms. Some of these definitions mirror the formulas for the real-valued exponential function. Specifically, one can still use the power series definition, where the real value is replaced by a complex one:

Using this definition, it is easy to show why  holds in the complex plane.

holds in the complex plane.

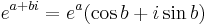

Another definition extends the real exponential function. First, we state the desired property  . For ex we use the real exponential function. We then proceed by defining only:

. For ex we use the real exponential function. We then proceed by defining only:  . Thus we use the real definition rather than ignore it.[6]

. Thus we use the real definition rather than ignore it.[6]

When considered as a function defined on the complex plane, the exponential function retains the important properties

for all z and w.

It is a holomorphic function which is periodic with imaginary period  and can be written as

and can be written as

where a and b are real values. This formula connects the exponential function with the trigonometric functions and to the hyperbolic functions. Thus we see that all elementary functions except for the polynomials spring from the exponential function in one way or another.

See also Euler's formula.

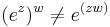

Extending the natural logarithm to complex arguments yields a multi-valued function, ln(z). We can then define a more general exponentiation:

for all complex numbers z and w. This is also a multi-valued function. The above stated exponential laws remain true if interpreted properly as statements about multi-valued functions. Because it is multi-valued the rule about multiplying exponents for positive real numbers doesn't work in general:

See failure of power and logarithm identities for more about problems with combining powers.

The exponential function maps any line in the complex plane to a logarithmic spiral in the complex plane with the center at the origin. Two special cases might be noted: when the original line is parallel to the real axis, the resulting spiral never closes in on itself; when the original line is parallel to the imaginary axis, the resulting spiral is a circle of some radius.

z = Re(ex+iy) |

z = Im(ex+iy) |

z = |ex+iy| |

Computation of ez for a complex z

If  , where x and y are real numbers, then

, where x and y are real numbers, then

Computation of ab where both a and b are complex

Complex exponentiation ab can be defined by converting a to polar coordinates and using the identity (eln(a))b = ab:

However, when b is not an integer, this function is multivalued, because θ is not unique (see failure of power and logarithm identities).

Matrices and Banach algebras

The power series definition of the exponential function makes sense for square matrices (for which the function is called the matrix exponential) and more generally in any Banach algebra B. In this setting, e0 = 1, and ex is invertible with inverse e−x for any x in B. If xy =yx, then ex+y = exey, but this identity can fail for noncommuting x and y.

Some alternative definitions lead to the same function. For instance, ex can be defined as  . Or ex can be defined as f(1), where f: R→B is the solution to the differential equation f′(t) = xf(t) with initial condition f(0) = 1.

. Or ex can be defined as f(1), where f: R→B is the solution to the differential equation f′(t) = xf(t) with initial condition f(0) = 1.

On Lie algebras

Given a Lie group G and its associated Lie algebra  , the exponential map is a map

, the exponential map is a map  satisfying similar properties. In fact, since R is the Lie algebra of the Lie group of all positive real numbers under multiplication, the ordinary exponential function for real arguments is a special case of the Lie algebra situation. Similarly, since the Lie group GL(n,R) of invertible n × n matrices has as Lie algebra M(n,R), the space of all n × n matrices, the exponential function for square matrices is a special case of the Lie algebra exponential map.

satisfying similar properties. In fact, since R is the Lie algebra of the Lie group of all positive real numbers under multiplication, the ordinary exponential function for real arguments is a special case of the Lie algebra situation. Similarly, since the Lie group GL(n,R) of invertible n × n matrices has as Lie algebra M(n,R), the space of all n × n matrices, the exponential function for square matrices is a special case of the Lie algebra exponential map.

The identity exp(x+y) = exp(x)exp(y) can fail for Lie algebra elements x and y that do not commute; the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula supplies the necessary correction terms.

Double exponential function

The term double exponential function can have two meanings:

- a function with two exponential terms, with different exponents

- a function f(x) = aax; this grows even faster than an exponential function; for example, if a = 10: f(−1) = 1.26, f(0) = 10, f(1) = 1010, f(2) = 10100 = googol, ..., f(100) = googolplex.

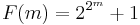

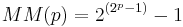

Factorials grow faster than exponential functions, but slower than double-exponential functions. Fermat numbers, generated by  and double Mersenne numbers generated by

and double Mersenne numbers generated by  are examples of double exponential functions.

are examples of double exponential functions.

Similar properties of e and the function ez

The function ez is not in C(z) (i.e., is not the quotient of two polynomials with complex coefficients).

For n distinct complex numbers {a1,..., an}, the set {ea1z,..., eanz} is linearly independent over C(z).

The function ez is transcendental over C(z).

See also

- e (mathematical constant)

- Characterizations of the exponential function

- Exponential field

- Exponential growth

- Exponentiation

- List of exponential topics

- List of integrals of exponential functions

- Tetration

References

- ↑ Goldstein, Lay, Schneider, Asmar, Brief calculus and its applications, 11th ed., Prentice-Hall, 2006.

- ↑ "The natural exponential function is identical with its derivative. This is really the source of all the properties of the exponential function, and the basic reason for its importance in applications…" - p.448 of Courant and Robbins, What is mathematics? An elementary approach to ideas and methods (edited by Stewart), 2nd revised edition, Oxford Univ. Press, 1996.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [1]

- ↑ Eli Maor, e: the Story of a Number, p.156.

- ↑ Walter Rudin, Real and Complex Analysis, McGraw-Hill, 3rd ed., 1986, ISBN 978-0070542341, page 1

- ↑ Ahlfors, Lars V. (1953). Complex analysis. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc..

External links

- Complex exponential function on PlanetMath

- Derivative of exponential function on PlanetMath

- Derivative of exponential function interactive graph

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Exponential Function" from MathWorld.

- Complex Exponential Function Module by John H. Mathews

- Taylor Series Expansions of Exponential Functions at efunda.com

- Complex exponential interactive graphic